“Just Right and Getting Better.” – The Legacy of Dr. C. Clayton Powell Sr

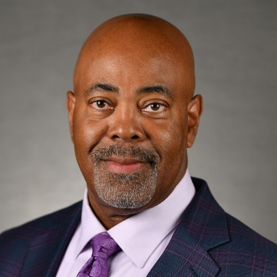

Biographical Sketch by Edwin C. Marshall, O.D., M.S., M.P.H.

ABSTRACT

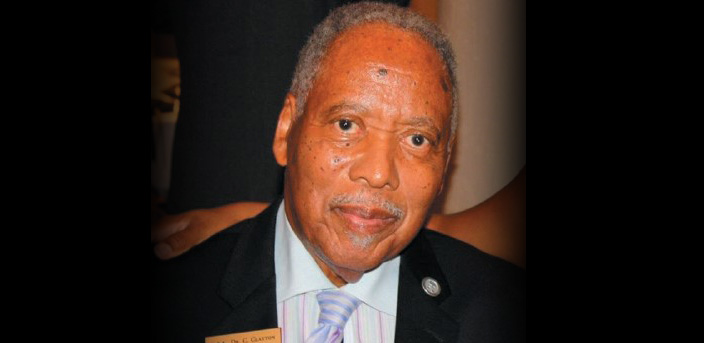

This paper presents a profile of visionary optometric and civic leader, Dr. C. Clayton Powell (1927-2020). After graduating from Morehouse College and Chicago College of Optometry, he entered optometry practice in Atlanta, Georgia, and embarked on a lifetime of service on both local and national stages. He is best known in optometric circles as co-founder and first president of the National Optometric Association.

“The tragedy of life doesn’t lie in not reaching your goal. The tragedy lies in having no goal to reach. It isn’t a calamity to die with dreams unfulfilled, but it is a calamity not to dream. It is not a disaster to be unable to capture your ideal, but it is a disaster to have no ideal to capture. It is not a disgrace not to reach the stars, but it is a disgrace to have no stars to reach for. Not failure, but low aim is sin.”

—Benjamin Elijah Mays

The words of former Morehouse mentor and president Dr. Benjamin E. Mays were not wasted on alum Cleo Clayton Powell. For him, low aim was never an issue; the bar was always high with a vision to see new horizons and create new journeys. He was a man of conviction with a resolute spirit that dared the mainstream of status quo. He blazed trails that did not exist and achieved his life’s purpose through goals that touched the sky and transcended the structural and social limits of his day. He was both a visionary and a reactionary, meeting every challenge and opportunity with care and understanding. While always confident, he probably did not anticipate with a full understanding or appreciation of the enormous influence he would wield–directly and indirectly–on the lives of aspiring youth and adults and in shaping the social, health and political landscape of one of the country’s largest and most diverse cities.

Cleo Clayton Powell was born April 11, 1927 in Dothan, Alabama. During his interview for the Morehouse College 150th Anniversary Oral History Project, he recalls days of picking cotton and shaking peanuts and attending North Highlands-Dothan

Colored School, which he described as a “broken down school…no laboratories, no libraries, no nothing…but some good teachers.”1 At the age of 15, following a fight with his stepfather, he moved to Atlanta, Georgia to live with his uncle and aunt in their three-room “shotgun house,” so-named because of its characteristic one-story, one-room wide, no-hallway, back-to-back room layout where it’s said if a shotgun shell was shot from the front door it would pass through each of the rooms and exit the backdoor without hitting anything.1,2

From a young age, Cleo Powell dreamed of being a high achiever and a game changer who would stand out in the crowd. “I possessed conquer-the-world confidence as early as my mid-teens,” he wrote.2 He excelled academically throughout elementary and high school. In Dothan, he was double-promoted from first grade to third grade; and in transitioning to Atlanta, he skipped from the ninth grade to the eleventh grade at Atlanta’s Booker T. Washington High School—the only high school for Black students in Atlanta at the time.1,2 His academic trajectory included being voted senior class salutatorian and receiving an offer of an academic scholarship to attend Morehouse College.

He first was made aware of Morehouse while in Dothan by his eighth-grade teacher who talked often and fondly about his alma mater on “the little red hill.”1,2 Even with the Morehouse scholarship, the Booker T. Washington salutatorian still needed money to succeed at college. Acting on an opportunity presented through a relationship between Morehouse College and the Connecticut tobacco industry, Cleo Powell took off to Hazardville, Connecticut to work the summer growing season on the L.B. Haas Tobacco Farm.1,2 He continued to work on the farm for eight straight summers, seven as a foreman. He also waited tables and clerked at the post office in Atlanta to support a moderate college social life.2

Cleo Powell entered his dream college in 1944. He was a Morehouse contemporary of Martin Luther King Jr., who also was his classmate at Booker T. Washington High School and who campaigned for him when he ran for Washington High School student body president. Cleo Powell continued on an aggressive path of scholarly and extracurricular activity. He joined the Morehouse College Glee Club and Omega Psi Phi Fraternity and was accepted into Beta Kappa Chi, national scientific honor society. After two successful years at Morehouse, he took a break from college to satisfy a recurring request from an aunt in Alabama who had been highly instrumental to his personal development.1,2 In the fall of what would have been his junior year, he headed to rural, southwest Alabama to join her at Burnt Corn Junior High School in Burnt Corn, Alabama. For one year, at the age of nineteen, he served as the assistant principal, taught seventh, eighth and ninth grade math and coached the boys’ basketball team.1,2 He returned to Atlanta in 1947 to finish his remaining two years of undergraduate study. Sixty-seven years later, on Alumni Day in 2014, Morehouse College acknowledged him with the Presidential Citation of Merit for his lifetime of service and extraordinary accomplishments as an optometrist and civic leader.

Cleo Powell attended Morehouse as a pre-med student with the intention of pursuing optometry after graduation. He was introduced to optometry while working mornings and afternoons before and after high school as a janitor for the R.M. Shaw Optical Company on historic Auburn Avenue.1,2 The company optometrist was Dr. H. E. Welton, the first Black graduate of The Ohio State University College of Optometry and the first Black optometrist to become a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry. Dr. Welton took a special interest in Cleo Powell, telling him about optometry and allowing the young janitor to follow him around and sit in on and observe one of his optometric examinations.1,2 That fortuitous association prompted Cleo Powell to consider optometry as a career alternative to his earlier thoughts of medicine and dentistry. Dr. Welton, who later relocated to Cleveland, Ohio turned out to be a lifelong mentor, friend and supporter.

Applying to schools of optometry transformed Cleo Clayton Powell into C. Clayton Powell, as he tells the story:

My senior year [at Morehouse] also marked one of my life’s defining personal resolutions. In replying to my admission applications, several schools of optometry, I noticed, addressed me as “Miss Powell”–obviously believing that Cleo Powell was a female. So, I remodeled my identity. I decided to thereafter go by the distinctive, robust handle of C. Clayton Powell.2

After graduating from Morehouse in 1949, C. Clayton Powell left Atlanta for Chicago to study optometry. He was accepted into the Northern Illinois College of Optometry (NICO) after being told by several other schools that, “We don’t accept Negroes.”1 An accreditation issue at NICO and a quick change of plans led him to be admitted as the only Black student in his class at the Chicago College of Optometry (CCO), which in 1955 merged with the Northern Illinois College of Optometry to become the Illinois College of Optometry (ICO).2 It was at the Chicago College of Optometry where he got to benefit from the guidance of Dr. Junius P. Brodnaxone of the first Black optometrist faculty members at an accredited U.S. school or college of optometry—and where he first met John Howlette, who was in the class ahead of him and who would become his optometry soulmate. As he had done in high school and college, optometry student Powell took full academic and professional advantage of his time at CCO, serving as co-editor of Eyes Right, the school newspaper, and as a member of both Beta Sigma Kappa International Optometric Honor Society and Tomb and Key Honor Society. An article on glaucoma he published in Eyes Right as a CCO student was subsequently republished in an issue of the Georgia Optometric Association Journal.2 In 1986, ICO honored Dr. Powell with an honorary doctor of science in optometry degree.

Following graduation from CCO in 1952, Dr. C. Clayton Powell returned to Atlanta and the persistent call of public service. He was a committed servant leader, confidently displaying his abilities early on as president of Atlanta’s Zion Hill Baptist Church Youth Group and being elected student body president of Booker T. Washington High School in a landslide victory after being at the school for only one year.2 Moving on to college and optometry school, he was elected basileus (president) of the Psi (Morehouse) Chapter of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity and president of the Beta (CCO) Chapter of Mu Sigma Pi optometric fraternity. Shortly into his professional life, he was elected vice president and later president of the Atlanta branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and secretary of the Georgia State Conference of NAACP Branches. As chair of the Legal Redress Committee, he worked with Thurgood Marshall—litigator of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education desegregation case and later justice on the U.S. Supreme Court—on investigating and supervising the litigation of school desegregation and other cases reported to the NAACP Atlanta branch.2

Dr. C. Clayton Powell was a formidable presence in both stature and personality. He made a loud noise that resonated against the boundaries of denial and crumbled the walls of exclusion. He ran for the Georgia House of Representatives and won the Republican primary in 1966 but lost in the general election.2 In 1972, he was a delegate to the Republican National Convention and a year later, he was named as a charter member of the Development Authority of Fulton County. Through his 41 years of transition across the roles of member, chairman and executive director of the development authority, he helped create jobs, promote economic growth and stimulate development opportunities, particularly for Atlanta’s Black community. As a forward-thinking member of the Fulton County Republican Executive Committee, he rose to become a significantly influential political power broker and civil rights advocate. He wrote:

I was a Republican, for sure. However, my support of the GOP in no way prevented me from supporting candidates of any political ilk, black or white, whom I deemed worthy. I took pride in being an independent thinker and a split-ticket voter. Sometimes that made sparks fly.2

His lifetime of civic engagement was recognized in 2017 with a proclamation from the Georgia House of Representatives.

Dr. Powell successfully merged a passion for civic service with his professional obligation as a practicing optometrist. He shared his time and talents between addressing the vision and eye care needs of his private office patients and providing optometric services to Morehouse College, Clark College, Morris Brown College, Spelman College, Atlanta University, Grady Hospital and the Atlanta Southside Comprehensive Health Center—one of the first neighborhood health centers in the country.2 He charted new territory that helped define the scope of public health for medically underserved people in Atlanta when he sat as the administrative head of the Atlanta Southside Comprehensive Health Center. As its executive director and one of the first optometrists nationally to be awarded the responsibility of heading a community health center, director Powell managed the health center’s $4 million annual budget and its more than 300 employees—an achievement that was not without great significance for organized optometry.2 But that was not enough for the dedicated civil servant. For 54 years, he was a devoted member of the board of directors of the not-for-profit Sadie G. Mays Health & Rehabilitation Center, which provides short- and long-term skilled nursing and rehabilitative services to the Atlanta community.3 Dr. Powell also was the first Black person and first practicing optometrist appointed to the National Eye Institute (NEI) National Advisory Eye Council at the National Institutes of Health, serving two four-year terms of advising on policies and activities related to NEI-supported research and programs and advocating for the vision health of inner-city patients.2

One of Dr. Powell’s greatest and surely one of his most gratifying and recognizable legacies is the National Optometric

Association (NOA), which he co-founded with his former CCO schoolmate, colleague and long-time friend, the late Dr. John L. Howlette. They called together Black optometrists from around the country to a meeting in May of 1969 in Richmond, Virginia, the hometown of Dr. Howlette. The meeting ended with the 25 attending optometrists having chartered and certified the first meeting of the NOA.2 The founding of the NOA was not without controversy and not a completely welcomed event within the larger circles of optometry. Some of those in opposition called it “a return to racial segregation,” but Dr. Powell was not daunted as he expounded the message of, “don’t let others’ inability to see our vision deter us from pursuing it.”2 It should be noted that while the NOA is predominantly an organization of Black optometrists, it does not exclude membership based on race or ethnicity and has had two Latinx presidents and a number of non-minority members, including deans and presidents of schools and colleges of optometry.

Drs. Powell and Howlette saw the NOA not as a splinter group or competition for the much larger, more established and mainly white American Optometric Association (AOA). They envisioned the NOA as a powerful, nationally representative voice for the issues important to Black and other minority optometrists—issues such as student recruitment and retention, new graduate placement and professional development. Since NOA’s founding, Black student representation at U.S. schools and colleges of optometry have increased 17-fold, with the NOA providing—through its National Optometric Foundation arm—over $500,000 in matriculation support, financial scholarships, vision and eye health education and awareness programs.4-6 Dr. Powell believed in reaching back and often welcomed recent graduates with opportunities to gain practical experience as associate practitioners in one of his three Atlanta offices. The co-founders also foresaw the NOA as a promoter of vision and eye care in minority communities and as a professional home for Black optometrists who were unable to join their state optometric association because of their race—as was the situation with co-founder Howlette.7 Although Dr. Powell was the first Black optometrist to join the Georgia Optometric Association, he asserted that AOA membership at the time for Black optometrists “amounted to taxation without representation.”2

Social commitment was one of the founding pillars of the NOA, often articulated by Dr. Powell through his impassioned preaching that optometry needed a “soul injection.” In his memoir, he recalled the following conversation that took place during the 1969 AOA National Optometric Conference [not affiliated with the NOA] in St. Louis, Missouri:

…some AOA board members displayed relative indifference as California Optometrist Dr. Clyde Oden [President and CEO of Watts Health Systems, Inc. in Los Angeles] and I gave a presentation on

the merits of locating Optometry practices within community comprehensive health centers. Clyde Oden did not suffer fools gladly. At a point during my discussion, he rapped the group for its nonchalance.

“What Dr. Powell is trying to give you is a shot of social consciousness,” he chided.

“Well, Clyde, just where is he going to give us that shot?” came

a devil-may-care question from the director of the AOA office in Washington, D.C.

“That all depends,” Clyde rebounded. “It depends on how you take what he’s presenting. If you take it properly, he’ll give it to you in your arm. Otherwise, he’ll give it to you in your backside.”2

That conversation ultimately led to the beginning of an interprofessional relationship between the AOA and NOA that started with a focus on the recruitment of Black students into optometry and the appointment of Black optometrists to AOA committees. It also led to then AOA president Melvin Wolfberg attending and addressing the 1970 NOA convention in Chicago, which registered twice as many optometrists as the charter meeting in Richmond the previous year.2 In turn, President Wolfberg invited Dr. Powell to give a plenary session presentation at the 1971 AOA convention in Hawaii.

Dr. Powell served as the NOA’s first president from 1969 to 1974. He guided the organization during its formative years with bold confidence and emotion, communicating its purpose with targeted precision for those who continued to question the need for its existence. His presidential duties consisted of organization management, clerical support, financial assistance, meeting planning and anything else that fell within the administrative purview of the nascent organization. The NOA conventions were a family affair, mostly orchestrated by Dr. Powell. The Saturday evening formal banquets during the early years usually lasted late into the night as Dr. Powell would go table by table and personally introduce from memory everyone sitting at each table—the NOA optometrists, their family members and their guests. Between conventions, he kept the membership informed via regular mailings of the NOA newsletter that he personally wrote, printed and distributed from his optometry office.

When three students from the Indiana University School of Optometry (IUSO) invaded his office in the spring of 1970 during a school-sanctioned recruitment tour of historically Black colleges and universities, Dr. Powell not only welcomed the students, but he introduced them to the NOA and invited them to attend the 1970 NOA convention in Chicago a few months later. Because of Dr. Powell’s personal invitation, the three from the IUSO were the first optometry students to attend an NOA meeting.

(Their presence most likely provided the gateway to greater student participation at future NOA meetings and the eventual establishment of the National Optometric Student Association.) The students were inspired by seeing so many Black optometrists and having direct access to their knowledge, advice and encouragement. One of the three students became the seventh president of the NOA and a vice president of Indiana University and another became dean of The Ohio State University College of Optometry.

Through the NOA, Drs. Powell and Howlette gifted the profession of optometry with new purposeful leadership and a mission that has for over five decades pressed an agenda of issues, policies and activities to advance the visual health of minority populations and increase racial and ethnic diversity within the profession. In recognition of their significant and enduring contributions to the optometric profession, they were jointly honored as the first Black optometrists to be inducted into the National Optometry Hall of Fame. Since their induction in 2001, the NOA has produced three additional Black optometrist inductees into the Hall of Fame and three NOA members have been named AOA national Optometrist of the Year, including two NOA past presidents. Reflecting Dr. Powell’s lifelong reach for high achievement, the NOA continually challenges its members to greater levels of professional and personal excellence.

In 2019, the NOA celebrated its 50th anniversary with members dutifully carrying forth the mantle of achieving a diverse and inclusive optometric profession and vision and eye health equity across all population groups. The anniversary convention paid special tribute to the history and legacy of Drs. Powell and Howlette with the theme of “NOA Forever: Past, Present and Beyond.” An emotional, 92-year-old Dr. Powell reflected over the previous 50 years and expressed profound pride in what the organization had become in producing a close family of diverse clinicians, educators and leaders for the optometric profession. His hope was that the NOA will continue to grow and develop as a collaborative professional resource for generations to come.

Dr. Powell lived a life full of engagement in promoting the well-being of those he knew, as well as those he did not know. Often described as commanding, distinguished, courageous, inspirational, pioneering, creative, independent, determined and bold, C. Clayton Powell—whether he was Optometrist Powell, Co-Founder Powell, President Powell, Executive Director Powell, Chairman Powell, Entrepreneur Powell, Political Czar Powell, Community Activist Powell or Mentor Powell—was guided by his embodiment of “spizzerinctum,” which he described as “the will, the hutzpah, the drive to succeed.”2 Dr. Arol Augsburger, former president of the Illinois College of Optometry, called Dr. Powell

“a champion of success” and Dr. William J. Williams, professor emeritus of the University of Southern California, wrote that “he brought honor and dignity to every situation.”2 However, Dr. Powell readily acknowledged that his successes were not his successes alone, but that they were built from “a community of outstanding mentors and role models:”

So many individuals have gone out of their way to offer me direction, mentorship, motivation, employment, loans, advice, pats on the back. Strangers and friends alike have blessed me beyond measure.2

Just as he was inspired by those within his community of mentors and supporters, C. Clayton Powell inspired others with compelling perspectives of empowerment toward personal accomplishment and professional success. He planted seeds of a different tree and will be forever tied to the fruits of those seeds and the lives they nourished. When a major stroke in 2001 at the age of 74 placed Dr. Powell in a wheelchair and forced him to retire from optometry after nearly 50 years of practice, he did not let it weaken his spirit or his resolve. His strong sense of purpose provided him with the spizzerinctum to continue to live and work productively as a venerated leader and mentor. When anyone asked how he was doing, it was not unusual for Dr. Powell to express his naturally positive attitude with a knowing smile and the spirited reply, “Just right and getting better.”8

On Friday, October 23, 2020, at the age of 93 years, the clock stopped for Cleo Clayton Powell Sr. Sixteen days later, the NOA’s virtual tribute, “Honoring an Icon in Optometry – Dr. C. Clayton Powell Sr.,” celebrated the life of Dr. Powell with personal reflections from leaders of the AOAn, American Academy of Optometry, Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry, National Optometric Association and National Optometric Student Association. Their admirations provided confirmation that Dr. Powell’s voice will not go silent and that the hands of time will continue to revere his applauded life.

AOA secretary-treasurer and chair of the AOA Diversity and Inclusivity Task Force, Jacquie M. Bowen noted on the AOA website:

He was a man who found solutions to problems and he was fearless when it came to pursuing new experiences. I hope we all honor his legacy by continuing the work he began toward expanding diversity in optometry and creating an environment where all are heard, and all perspectives are equally valued.9

NOA President Dr. Sherrol A. Reynolds commented on behalf of the NOA family:

Our profession has lost an icon and legend with the passing of the National Optometric Association’s cofounder and visionary leader, Dr. C. Clayton Powell. He co-created the NOA in order to open doors for African-American optometrists and students. The NOA has strengthened our profession, created new opportunities and promoted minority ocular health in underserved communities. Dr. Powell’s dedication to our profession is unparalleled and he will be deeply missed, but his legacy will continue forever.9

The physical distance Cleo Clayton Powell travelled from Dothan to Atlanta was only 200 miles, but the touchable distance of Dr. C. Clayton Powell’s indelible imprint on the face of optometry and society defies calculation. His life’s journey authenticated him as a legend in the historical annals of optometry and in the pursuit of social justice. He reached for his goals, fulfilled his dreams and captured his ideals. Such was the life of Dr. C. Clayton Powell Sr. His legacy is undeniable and his light will continue to shine on the future he imagined. To paraphrase Maya Angelou’s When Great Trees Fall, Dr. C. Clayton Power existed and we can be better for he existed.

REFERENCES

- Interview with Dr. C. Clayton Powell ’49 [Internet]. Atlanta, GA: Morehouse College 150th Anniversary Oral History Project; published April 24, 2012 [cited 2021 Dec 7]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9-NuGkukx3g.

- Powell CC, Winbush DE. C. Clayton Powell and the real Atlanta: a memoir and a tribute to those who made it happen. Alpharetta, GA: BookLogix; 2019.

- Farewell, Dr. Powell [Internet]. Atlanta, GA: Horizons – The Newsletter of Sadie G. Mays Health & Rehabilitation Center; 2020 October;10(3):2 [cited 2021 Dec 19]. Available from: Horizons-Fall-2020.pdf (sgmays.org).

- Chen EE. Comparing proportional estimates of U.S. optometrists by race and ethnicity with population census data. Optometric Education. 2012 Summer;37(3):107-114.

- Annual student data report: academic year 2020-2021

[Internet]. Rockville, MD: Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry; published May 2021 [cited 2021 Dec 21]. Available from: https://optometriceducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/ASCO-Student-Data-Report-2020-21.pdf. - National Optometric Foundation, Inc. [Internet]. Charlotte, NC: National Optometric Association; [cited 2021 Dec 27]. Available from: https://nationaloptometricassociation.com/foundation/.

- Howlette J. Personal communication with Edwin Marshall.

- Powell Sr., Dr. C. Clayton [Internet]. Atlanta, GA: The Atlanta Journal-Constitution; published October 31, 2020 [cited 2021 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.ajc.com/news/obituaries/powell-c/26UWCPMD2RC2ZC2HUROX4HUUDU/.

- C. Clayton Powell, O.D., trailblazer for diversity within optometry, dies [Internet]. St. Louis, MO: American Optometric Association; published October 28, 2020 [cited 2021 Dec 3]. Available from: https://www.aoa.org/news/inside-optometry/member-spotlight/c-clayton-powell-od-obit?sso=y.